It is a myth that is, despite being debunked in the 1970s, still rampant – still passed smugly between schoolchildren in playgrounds all over Australia. It was certainly something I believed for a long time, and is still circulated in popular culture, including in the 2016 blockbuster Arrival – a film with a linguist protagonist, as well as several high-profile linguistics consultants.

I am talking about the Australian furphy around the etymology of kangaroo – that it actually means ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I don’t understand you’ in language. The story goes that while exploring an area of far north Queensland, near modern-day Cooktown, Lieutenant James Cook and Joseph Banks encountered an unfamiliar creature and tried to ask a local Guugu Yimidhirr man what it was called. He responded, ‘I don’t know’ and the Englishmen took this to be the creature’s name.

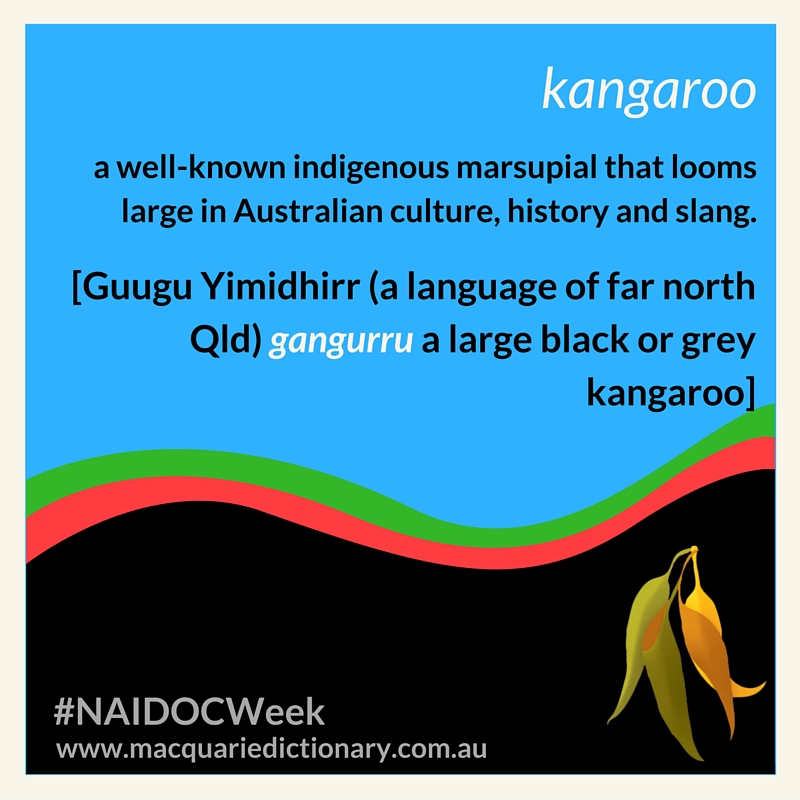

As it may not surprise you to hear, this is not the case. In reality, kanguru (pronounced ‘kang-uru’), or ganguru (‘gang-uru’) since k and g are in free alteration in Guugu Yimidhirr, refers to the male of a large black or grey kangaroo species – one of at least eight varieties of kangaroo distinguished in the language.

The myth can be traced back to Captain Phillip King, who visited the area in 1820. He established good relations with the Guugu Yimidhirr people and compiled a vocabulary for the language that agreed with Cook’s on all words except one: He recorded a different word for ‘kangaroo’ – menuah. It is thought that King was actually given the word minha, a generic term for ‘edible animal’, but still, King’s account led people to speculate about the actual meaning of kangaroo in Guugu Yimidhirr.

Another interesting chapter in the story of kangaroo is that when the First Fleet arrived in Sydney in 1788, they used the word kangaroo with local Dharug people, not realising at first that they spoke a different language. The Dharug people adopted kangaroo, thinking it was an English word for ‘edible animal’ and apparently even inquired as to whether cows were kangaroo. This is a common pattern in the history of contact between English and Australian languages – words spread between Indigenous languages through contact with English. In fact, several decades later, speakers of the Baagandji language of northern New South Wales also acquired the word through contact with European settlers. Baagandji people started using the form gaaŋgurru in order to describe a strange new animal – the horse.

Perhaps, then, the myth is so pervasive because it does represent something true about the story of kangaroo, and in fact many other loan words from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages: That the process of borrowing from Australian languages is so often characterised by miscommunication.